Minimum DataBase

A Leishmania case study: Bella

Background information

Name: Bella

Age: 1 year

Breed: Collie Cross

Gender: Female entire

Presenting reason

Stiffness/Lameness and Pyrexia

History

Three-week history of stiffness when rising and lameness with 12-hours of pyrexia. Episodes of small intestinal diarrhoea in the last month which have resolved. She was rescued from Spain 8-months earlier.

Physical examination

Quiet but responsive with pyrexia (39.5oC) and tachycardia (140pm), ventral pyoderma, palpable joint effusions and pain on flexion and extension of carpi, tarsi and stifles. Body condition score 4/9, weight 19.5kg.

Diagnostic plan

A minimum database (MDB) comprising haematology, biochemistry, electrolytes and urinalysis was performed in view of her pyrexia and joint effusions and history of living in Spain. C-reactive protein (CRP) was assessed in view of the joint effusions as a marker of systemic inflammation and blood was submitted or quantitative serology and PCR for Leishmania and a SNAP 4DX (Heartworm antigen, Lyme antibody, Ehrlichia antibody, Anaplasma antibody).

In addition, under general anaesthesia, radiographs of the affected joints were performed, synovial fluid was aspirated from the left hock, carpus and stifle and submitted for analysis. Abdominal ultrasound was also performed.

Interpretation of results of diagnostic tests

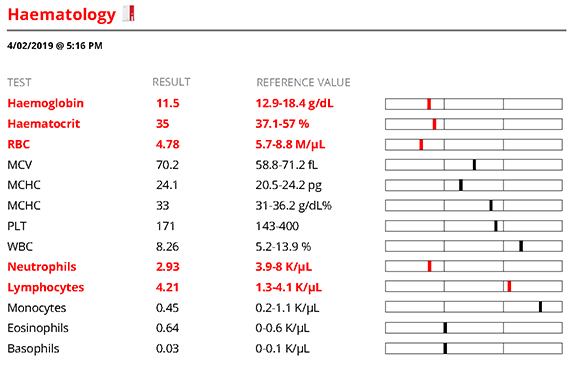

Haematology showed a mild non-regenerative anaemia which is likely secondary to the underlying problem, a mild lymphocytosis which might be related to antigenic stimulation (no abnormal cells seen on smear review) and a neutropenia which is likely secondary to consumption due to an inflammatory process but could be related to destruction or lack of bone marrow production.

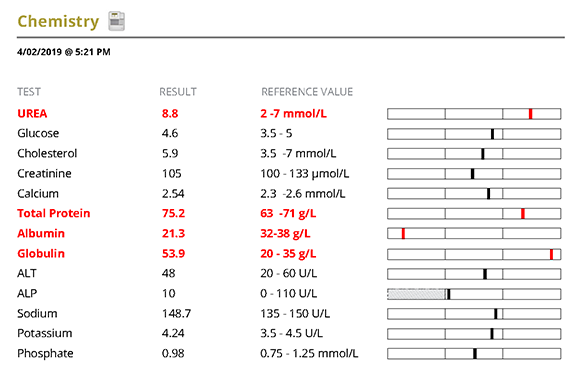

Biochemistry showed a mild elevation in urea which may be due to dehydration, protein meal, gut bleeding or renal disease. There was also elevation of total protein with hyperglobulinaemia likely reflecting an inflammatory protein response. Hypoalbuminaemia which is consistent with protein loss via either the gut/kidneys, lack of production from the liver and a component of acute phase protein response.

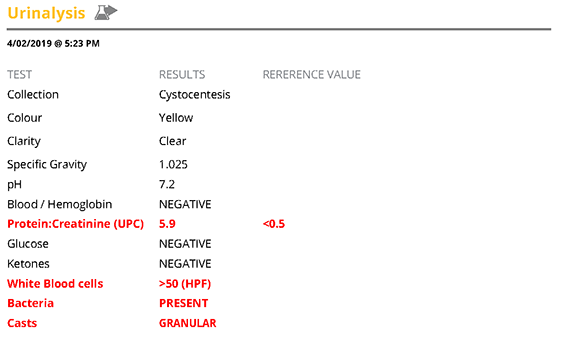

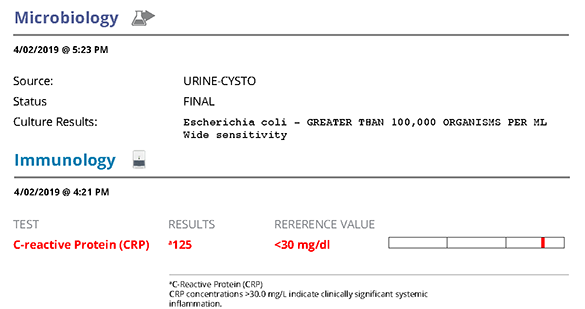

Urinalysis confirmed proteinuria (UPC 5.9; <0.5) and is a likely cause for the hypoalbuminaemia. The UPC should normally be confirmed as a persistent finding, however at this level it is not simply due to infection/pre-renal causes and can be treated as a protein-losing nephropathy. The urine was sub-maximally concentrated (USG 1.025) which would suggest the elevation in urea may be renal in origin. SDMA would have been useful as an additional indicator of glomerular perfusion. There was a urinary tract infection present (positive urine culture for E.coli; inflammatory sediment; bacteriuria) which requires addressing in the treatment plan.

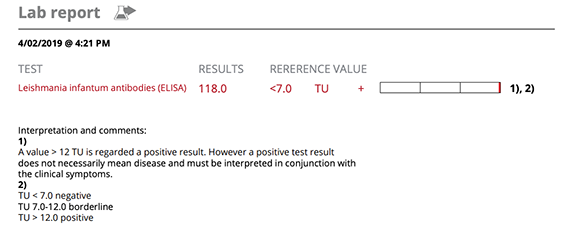

Leishmania infection was confirmed with a high positive titre (118 elisa test units [TU]) and blood PCR was also positive for Leishmania DNA. The SNAP 4Dx was negative excluding several common co-infections.

Joint fluid analysis confirmed marked neutrophilic inflammation in all joints with no micro-organisms seen and culture was negative. Joint radiographs confirmed the effusion with no evidence of erosive disease. These changes are consistent with an inflammatory/immune arthropathy likely related to the leishmania infection.

C-reactive protein (CRP) was markedly elevated (125; <30mg/dl) confirming systemic inflammation and providing a marker for monitoring response to treatment.

Patient reports

Treatment plan

In view of the high leishmania antibody titre, clinical signs arising from immune complex disease (glomerulonephritis, polyarthritis), nonregenerative anaemia, hyperglobulinaemia, hypoalbuminaemia and Iris Stage I proteinuric kidney disease (marked proteinuria UPC>5) this would stage the dog as III/IV on the Leishvet staging system (Solano-Gallego et al, 2011). Treatment was based upon Leishvetand IRIS guidelines.

Treatment of the leishmania included miltefosine at 2mg/kg orally for 28 days alongside allopurinol at 10mg/kg twice daily longer term. Benazepril was prescribed for the proteinuria at 0.5mg/kg once daily and aspirin at 0.5mg/kg once daily to reduce thrombotic risk (clopidrogel would be a suitable alternative). Although polyarthritis can be caused by leishmania infection (true infective arthritis) it can also be driven by immune complex disease. In view of the severity of the joint effusions and the severe inflammatory component with no evidence of leishmania amastigotes in the synovial fluid, the dog was treated with prednisolone initially at 1mg/kg twice daily and reduced every 5 days and stopped after 3 weeks based on clinical response. Ongoing treatment of the leishmania was enough to control the inflammatory arthropathy.

The urinary tract infection and pyoderma were treated with Cephalexin at 20mg/kg twice daily for 10 days and repeat urine culture was negative and the pyoderma resolved.

Follow up

An MDB was performed after 3 weeks of treatment and showed resolution of the neutropenia, resolving anaemia and improving albumin (25.2g/l). The UPC remained elevated at 4.62 and therefore benazepril was increased to 1mg/kg once daily. CRP was normal (8.2mg/dl) and the dog was significantly improved clinically.

The UPC became normal on the increased dose of benazepril and with treatment of the leishmania. Urinalysis revealed xanthine crystals after 5months of treatment and a low purine diet was then fed. After 5 months of treatment the dose of benazepril was reduced and subsequently stopped when the UPC remained <0.1. Aspirin was also stopped. UPC was followed at subsequent checks and after completion of treatment of leishmania and remained <0.1.

Leishmania serology was reassessed after 6 months (56 TU) and 12 months (20 TU) showing encouraging reduction. Allopurinol was continued and repeat serology at 18mths showed antibody level 8 TU which is a negative result. At recheck 12 months later, the titre remained negative and the dog remained in clinical remission off all treatment

Comments

Diagnosis of leishmania can be challenging due to the spectrum of clinical signs and laboratory changes, the prevalence of subclinical infection and the advent of vaccines in endemic areas or in travelling pets. Leishmania serology is normally used for diagnosis and monitoring in clinical cases. A high antibody titre, with compatible clinical signs and laboratory abnormalities, in a non-leishmania-vaccinated dog are strongly diagnostic of disease. In-house serological tests are available and have acceptable specificity, however the sensitivity is variable and can be affected by stage of infection. In patients with compatible clinical signs the sensitivity is higher than in patients with subclinical infection.

These tests are qualitative (positive/negative) and can be used to screen patients but positives should be followed up with a quantitative test at a reference laboratory. The influence of vaccination on serology is vaccine specific and for further information consult Solano-Gallego et al, 2017. Leishmania PCR, in this case, was performed on blood and whilst positive, studies have shown that the sensitivity is higher on lesional tissue (e.g. skin lesions) or nasal or conjunctival swabs and therefore these would be advised in preference to blood PCR in clinical cases. Cytology or histology of lesional tissue can also be used to demonstrate the presence of organisms (amastigotes).

There are several different treatment options for leishmania including the protocol used here (Miltefosine and Allopurinol). Allopurinol predisposes to the formation of xanthine crystals and potentially stones, it is recommended to feed a low purine diet for the duration of treatment. In this case, it was only started after crystals were seen on urinalysis as cost of the diet had been considered prohibitive by the client.

This case demonstrates the importance of knowledge of travel history in identifying potential underlying causes in dogs presenting with condition such as polyarthritis. It is important to address concurrent disease such as the protein-losing nephropathy specifically in the treatment plan. Although the prognosis in this case was guarded to poor based on the Leishvet group staging scheme (Solano-Gallego et al, 2011), this was a rewarding case with all signs going into remission. This dog should be monitored every 6-12 months for recurrence of the leishmania infection.

Leishmania in an increasingly common diagnosis in UK dogs due to pet travel and there is a recent report of the infection in a non-travelled UK dog that was in contact with an infected dog (McKenna et al, 2019, Vet Record).

References

- McKenna, M., Attipa, C., Tasker, S., Augusto, M. (2019) Leishmaniosis in a dog with no travel outside of the UK.Veterinary Record doi:10.1136/vr.105157

- Silvestrini, P. Leishmaniosis in dogs and cats(2019). In Practice, 41, 5-14 doi:10.1136/inp.k5122

- Solano-Gallego L, Miró G, Koutinas A, Cardoso L, Pennisi MG, Ferrer L, Bourdeau P, Oliva G, Baneth G,. (2011) LeishVet guidelines for the practical management of canine leishmaniosis. Parasites & Vectors. May 20;4:86. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-86.

- Solano-Gallego L, Cardoso L, Pennisi MG, Petersen C, Bourdeau P, Oliva G, Miró G, Ferrer L, Baneth G. (2017) Diagnostic challenges in the era of Canine Leishmania infantum vaccines. Trends in Parasitology,33;9, 706-717 doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2017.06.004