Minimum DataBase

A diarrhoea case study: Henry

Background information

Name: Henry

Age: 10 years

Breed: Staffordshire Bull Terrier

Gender: Male neutered

Presenting reason

Chronic weight loss and diarrhea for two months.

History

Henry had a two-month history of intermittent small-intestinal diarrhea (voluminous yellow stools produced 3-4 times daily). He had lost 16% bodyweight despite a normal appetite and exercise. Vaccinations and treatment for endoparasites was up to date.

Physical examination

Henry was bright, alert and responsive and was normally hydrated but was in thin body condition (2/9). Thoracic auscultation was unremarkable with a normal heart rate and sinus arrythmia. Abdominal palpation revealed prominent intestines but was otherwise tolerated well. He was normothermic.

Initial interpretation and diagnostic plan

The most specific problem was chronic diarrhoea. The weight loss and poor body condition were likely to be secondary to the underlying problem.

Enteric causes of chronic small-intestinal diarrhoea are most common and include inflammatory bowel disease, enteric infection (pathogenic bacteria, parasites, fungi, viruses), dietary intolerance, partial obstruction (e.g. tumour, foreign body), lymphangiectasia and lymphoma. Extra-intestinal causes of diarrhoea include hepatic, renal or exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, hypoadrenocorticism or motility disorders.

Initial diagnostic tests included a Minimum DataBase (Haematology, Biochemistry, Electrolytes and Urinalysis).

Interpretation

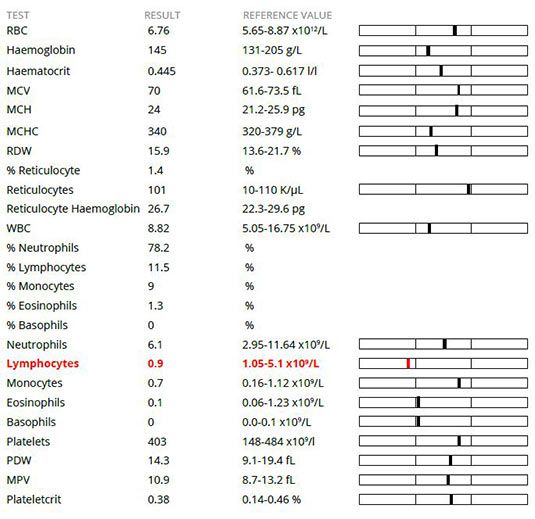

Haematology revealed a mild lymphopenia which is commonly caused by circulating corticosteroids (stress, hyperadrenocorticism, medication) but could also be due to loss via loss of lymph (e.g. protein-losing enteropathy, chylous effusion).

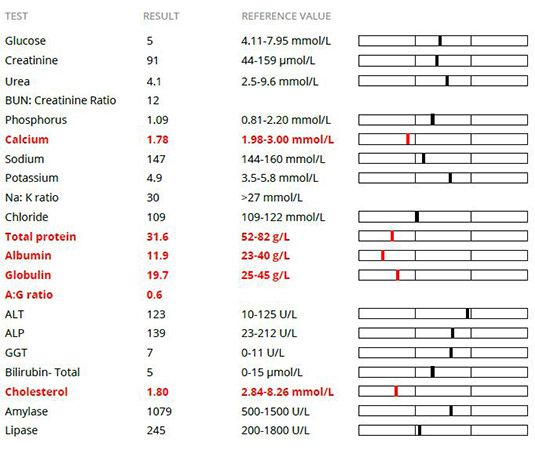

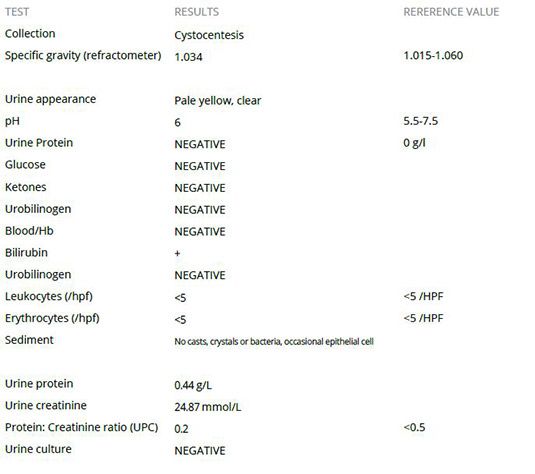

Biochemistry revealed a severe pan-hypoproteinaemia, mild hypocalcaemia and moderate hypocholesterolaemia. Urinanalysis was unremarkable.

Pan-hypoproteinaemia (albumin and globulin) may be most likely to arise due to protein-losing enteropathy (most commonly due to severe inflammatory bowel disease, infiltrative intestinal neoplasia or lymphangiectasia). Hepatic insufficiency was less likely as this would typically cause hypoalbuminaemia only and may also lead to low urea, glucose and hyperbilirubinaemia. There was no evidence of urinary protein loss contributing to the hypoproteinaemia.

Total hypercalcaemia was suspected to be due to hypoalbuminaemia (50% calcium is protein-bound but the ionized portion is responsible for physiological hypocalcaemia).

Hypocholesterolaemia may most likely be due to through loss of lymph (chylous effusion or lymphangiectasia) as there was no other evidence of hepatic insufficiency.

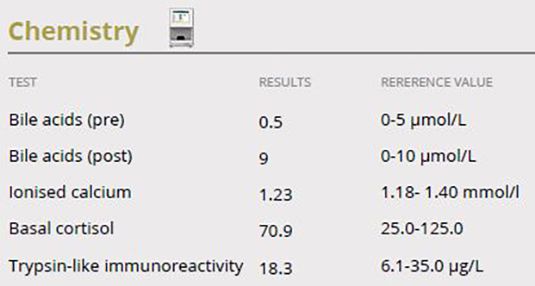

The clinical findings and minimum database results were suggestive of a protein-losing enteropathy/ lymphangiectasia. The minimum database enabled renal insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, proteinuria to be ruled out. Hepatic insufficiency was less likely. The normal electrolytes and low lymphocyte count made hypoadrenocorticism unlikely1.

Further testing helped to confirm that hypercalcaemia, hepatic and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and hypoadrenocorticism were not present as these results fell within the normal range.

The results were suggestive of a protein-losing enteropathy causing the clinical signs although a chylous effusion was also possible.

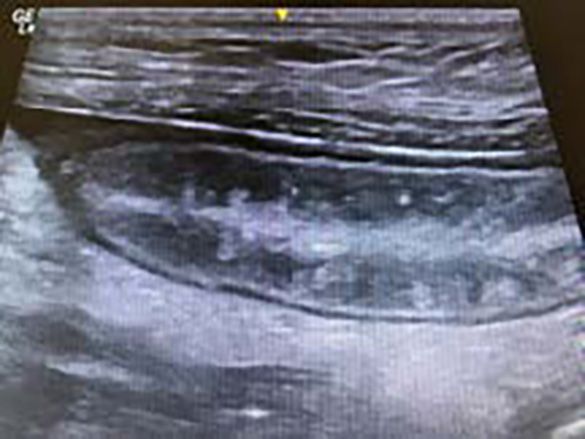

Abdominal ultrasound was performed under sedation which revealed a small volume of ascites and generalized small intestinal wall thickening with mild jejunal and duodenal lymphadenopathy. The intestinal mucosa demonstrated radial striations which can be suggestive of intestinal lymphangiectasia2

Abdominocentesis was performed and fluid analysis revealed a pure transudate with a few reactive mesothelial cells present. This finding is consistent with hypo-albuminaemia and ruled out a chylous effusion.

Due to the suspicion of an enteropathy, further testing was performed to assess for malabsorption.

Serum folate and cobalamin concentrations were low, consistent with proximal and distal intestinal malabsorption. Subsequent faecal testing was negative for parasites and bacteria.

Following a plasma transfusion for oncotic support, esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed as full-thickness biopsies may carry the risk of intestinal dehiscence3. The intestinal lumen had a typical appearance of lacteal dilatation with white mural plaques also present. Partial-thickness biopsies were taken.

Histopathology indicated lymphocytic-plasmacytic enteritis likely causing secondary intestinal lymphangiectasia. This combination can cause lymphopenia, non-selective enteric protein loss causing pan-hypoproteinaemia and fat malabsorption with disrupted chylomicron transport leading to hypocholesterolaemia.

Initial diagnostic tests

Haematology

Chemistry

Urinalysis

Follow-up tests

Interpretation

The dog was placed on a proprietary easily digestible, highquality protein, low-fat diet, supplemented with medium-chain triglycerides, to minimize lymphatic congestion.

Prednisolone was administered at 1mg/kg twice daily then was slowly tapered to maintenance at 0.5mg/kg every other day as clinical signs improved over subsequent months.

Cobalamin was administered at 750 µg by subcutaneous injection weekly for 4 weeks then monthly for a further 3 doses by which time the diarrhoea had resolved. Folate was supplemented at 400 µg orally once daily for 4 weeks. Serum levels of both vitamins normalised.

Regular endo-parasiticide treatment was continued following a course of fenbendazole at 50mg/kg once daily for 5 days.

Clopidogrel was administered at 2mg/kg PO q24h as protein-losing enteropathy may lead to a hypercoagulable state and development of thromboses.

Outcome

Henry remained bright in himself and the faeces became more formed and normalized by 6 weeks. He gained weight and his body condition returned to normal. He was still doing well without obvious progression of disease at 1 year. However, this presentation carries a guarded long-term prognosis4.

In this case, the initial clinical findings and minimum database results were suggestive of a protein-losing enteropathy and raised the suspicion for secondary intestinal lymphangiectasia. The minimum database allowed other major differentials to be excluded and further testing helped to clarify the type and extent of the underlying disease.

References:

- Seth M, Drobatz KJ, Church DB, et al. White blood cell count and the sodium potassium ratio to screen for hypoadrenocorticism in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2011; 25:1351-1356

- Sutherland-Smith J, Penninck DG, Keating JH, et al. Ultrasonographic intestinal hyperechoic mucosal striations in dogs are associated with lacteal dilation. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2007; 48:51-57.

- Shales CJ, Warren J, Anderson DM, et al. Complications following full-thickness small intestinal biopsy in 66 dogs: a retrospective study. J Small Anim Pract 2005; 46:317- 321.

- Zoran D. Protein-losing Enteropathies. In: Bonagura JD, Twedt DC, eds. Kirk’s Current Veterinary Therapy XV. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2014: 540-544.