Minimum DataBase

Case study: Jess

Courtesy of Kate Murphy BVSc (Hons) DSAM DipECVIM-CA FRCVS PGCert (HE), IDEXX Internal Medicine Consultant

Background information

Name: Jess

Age: 3 years

Breed: Labradoodle

Gender: Female neutered

Main presenting reasons:

- Chronic lethargy

- Acute haemorrhagic diarrhoea

- Chronic small intestinal diarrhoea

- Acute vomiting

- Acute collapse

History

Jess had a long-standing history of small intestinal diarrhoea with occasional colitis. She had been lethargic for six weeks but 24-hours prior to referral she developed acute haemorrhagic diarrhoea, vomiting and progressive collapse. Prior to referral, she had received intravenous fluid therapy at the referring practice. Her vaccinations, worming and ectoparasite control were up to date.

Physical examination:

- Temperature: 37.4oC

- Heart rate: 85 bpm

- Respiratory rate: 20 pm

- Capillary refill time: >2 seconds

Mucous membranes were pale and tacky. Peripheral pulses were weak but synchronous with the heart rate. There was discomfort on abdominal palpation and blood dripping from her anus.

Diagnostic plan

In view of the relative bradycardia and clinical signs consistent with hypovolaemia and dehydration the following actions were taken: intravenous access was obtained, blood samples for laboratory testing were collected before any treatment, blood pressure was measured (100mmHg systolic) and intravenous fluids were administered via boluses to address the hypovolaemia and more slowly to address dehydration.

Blood samples were used for full haematology, serum biochemistry and measurement of electrolytes. Ideally urinalysis would have been performed but the bladder was relatively empty at presentation.

Results of laboratory tests

The red blood cell and platelet counts were within normal limits. There was leukopenia due to neutropenia.

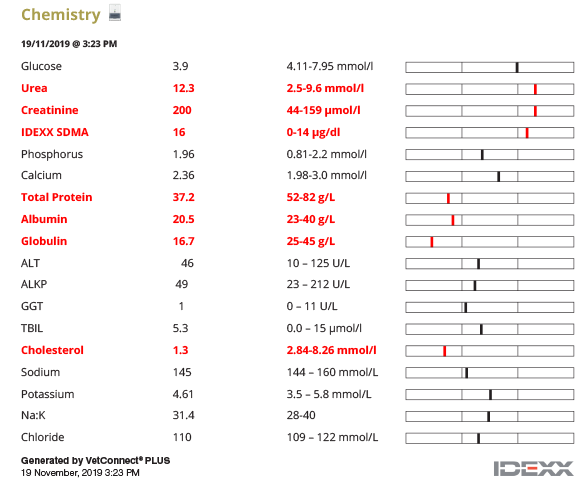

Serum biochemistry revealed mild elevations of SDMA, urea and creatinine, hypoproteinaemia due to hypoalbuminemia and hypoglobulinaemia and hypocholesterolaemia and sodium to potassium ratio was within normal limits.

Interpretation of laboratory test results

The normal platelet count excludes thrombocytopenia as a cause of the gastrointestinal bleeding. Coagulation times were not assessed but could have been useful to exclude other systemic bleeding causes before considering the possibility of an intestinal or infectious cause.

Neutropenia can indicate lack of production, overwhelming consumption/utilisation or destruction of neutrophils. It is worth bearing in mind that the lymphocyte and eosinophil counts were within reference intervals (absence of a stress leukogram) despite the collapsed state of the dog.

The mild azotaemia and elevated SDMA could be secondary to dehydration/hypovolaemia (pre-renal) or reflect renal or post renal causes. Pre-renal was considered likely given the clinical examination and history. Urinalysis would have been helpful to further assess this, however the bladder was too small to obtain a sample and fluids had already been given at the referring practice. The fluid therapy before referral may have impacted on the blood results at presentation.

In this case, the hypoalbuminaemia most likely reflected the loss of albumin due to acute gastrointestinal bleeding, however loss due to an underlying protein losing enteropathy cannot be excluded. Protein loss via the urogenital tract or decreased hepatic synthesis would typically result in hypoalbuminemia without hypoglobulinaemia.

Further investigations

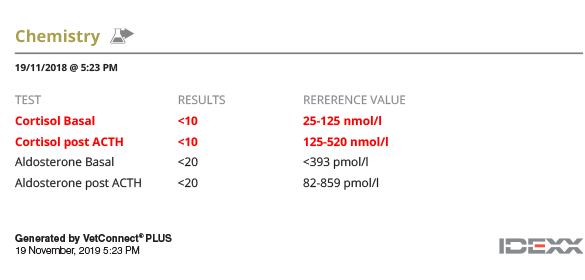

Although electrolyte concentrations were normal, the relative bradycardia, lack of stress leukogram, mild azotaemia and collapse led to clinical concern for hypoadrenocorticism. An ACTH stimulation test was performed and revealed undetectable levels of cortisol pre and post administration of intravenous tetracosactide (Dechra) at 5µg/kg confirming the presence of hypocortisolaemia. Since the electrolytes were normal at presentation, it was unclear whether this dog needed mineralocorticoid in addition to glucocorticoid supplementation. Aldosterone was therefore measured on the pre and post ACTH samples; both aldosterone results were subnormal indicating lack of response to stimulation thus confirming a lack of mineralocorticoid production. Primary hypoadrenocorticism /Addison’s disease was diagnosed.

In view of the acute haemorrhagic diarrhoea and leukopenia which are unusual in Addison’s disease, (Snead et al, 2011), a SNAP Parvo test (Idexx) was performed which was negative. Other infectious causes of acute haemorrhagic diarrhoea were considered as the hypoproteinaemia and neutropenia were more severe than typically seen in Addison’s disease and there was an outbreak of Leptospirosis locally at the time. Leptospirosis serology was performed using the original blood sample (acute period) revealing no significant elevation in the antibody titres of the serovars tested. However, the PCR test (EDTA blood sample) detected the presence of DNA confirming acute infection with pathogenic leptospires.

Once Jess was clinically stable, abdominal ultrasound was performed which showed moderate distension of the caecum and colon with anechoic fluid. Although the overall wall thickness was within normal limits, there were diffuse changes in the jejunal wall layering (muscularis and submucosal layers). The jejunal lymph nodes were slightly enlarged and irregular but were considered most likely to be reactive. The adrenal gland measurements were slightly smaller than normal.

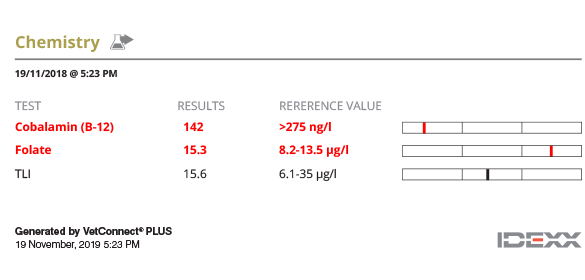

In view of the ultrasonographic findings and the report of chronic diarrhoea, serum TLI, cobalamin (vitamin B12) and folate were measured to assess intestinal function; decreased cobalamin and folate suggestive of diffuse small intestinal disease and malabsorption were present.

Diagnostic tests

Diagnosis

Hypoadrenocorticism

Leptospirosis

Diffuse small intestinal disease

Treatment plan

At admission, Jess was hypovolaemic and hypotensive as well as dehydrated. Blood gas analysis showed a metabolic acidosis (pH 7.189; ref. interval:7.35-7.44) and increased lactate (4.75 mmol/L; ref. interval:<2.0). Bolus (10ml/kg over 10minutes) intravenous fluid administration was given with Hartmann’s to correct the acidosis and volume deficits. After receiving 30ml/kg, the pulse volume improved, the pH increased, and lactate normalised. The fluids were then administered at 6ml/kg/hr for another 6 hours, then titrated down and stopped after 2 days. Fluid input and output as well as perfusion and hydration were monitored to ensure that the fluid balance was optimal.

After the diagnosis of hypoadrenocorticism, dexamethasone at 0.3mg/kg was immediately administered intravenously. Twelve hours later, oral treatment with prednisolone at 0.35mg/kg twice daily was instigated. Gradually over the next 2 weeks, the prednisolone dose was reduced to 0.15mg/kg once daily and administered long-term.

Zycortal (Dechra) was administered subcutaneously at 1.2mg/kg after the aldosterone results were obtained and electrolytes were checked at 10- and 28-days post injection.

Vitamin B12 supplementation was given by SC injection weekly for 6 weeks and then monthly for the following 6 months. Folate supplementation was not considered to be indicated.

Leptospirosis was treated initially with amoxicillin clavulanic acid at 20mg/kg twice daily intravenously for 3 days and then Jess was prescribed doxycycline at 5mg/kg twice daily for 2 weeks to reduce renal carriage and excretion of leptospires.

Follow up

Twenty-four hours post admission, the HCT had decreased to 37.5% and the neutrophil count had normalised (10.78x109/L).

Ten days post-Zycortal (Dechra) the electrolyte levels were indicative of good control. The Zycortal injection was repeated at 28-day intervals longer term as the electrolytes remained stable and the dog was clinically well. It was recommended to check electrolyte concentrations every 4 to 6 months.

Cobalamin and folate were measured after 6 months of B12 supplementation and were within normal limits. As the clinical signs had resolved with the treatment of hypoadrenocorticism, further investigation for concurrent intestinal disease was not carried out.

Prognosis/Comments

Hypoadrenocorticism/Addison’s disease is an uncommon endocrine disease but is easily treatable making it a rewarding medical diagnosis. This case was unusual in that she presented with acute collapse but had normal electrolytes. This may have been due to intravenous fluids administered before referral which masked the changes or could have been due to glucocorticoid deficiency alone (Atypical Addison’s). Most of the clinical and laboratory test findings can be explained by this diagnosis, although the neutropenia and severity of the hypoproteinaemia were considered unusual. The diagnosis was confirmed with an ACTH stimulation test and subsequent pre and post ACTH aldosterone measurement. The ACTH stimulation test should be ideally done at presentation once the patient is stabilised, although it can be performed after the administration of dexamethasone as this is not measured by the cortisol assay. It is inadvisable to do this test after several days or more of treatment as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis can be affected and interpretation of the ACTH stimulation test results will become more difficult. An alternative to measurement of aldosterone would have been to measure endogenous ACTH levels but this was not done in this case.

Mineralocorticoid deficiency was confirmed in this case by measurement of aldosterone levels. Long-term treatment with DOCP (Zycortal, Dechra) and prednisolone can result in an excellent prognosis. Prednisolone dose should be increased during periods of “stress” and it is advisable to do this for several days before and after the stressful period. Zycortal (Dechra) was used below the licensed dosed based on the clinician’s experience and after discussing with the clients the potential side effects associated with the higher licensed dose.

Leptospirosis is a potentially zoonotic bacterial infection, it has worldwide distribution and is of increasing global importance. It typically causes acute kidney and liver disease but can affect most organ systems and dogs can present with haemorrhagic gastroenteritis. Diagnosis can be made using serology (measurement of antibody titres) and typically a titre >1:800 for a serovar is consistent with infection. However, in acute infection negative titres can be seen and thus re-testing after 10-14 days is recommended in order to demonstrate a rising titre. In Jess’ case, this was not performed since leptospiral DNA was detected in the blood by the PCR (confirmatory for infection with pathogenic bacteria) and the client declined further testing for financial reasons. The European Consensus guidelines were followed for treatment of this patient (Schuller et al 2015).

Diagnosing concurrent leptospirosis in this dog would have probably not been considered without taking into account the neutropenia but most importantly the history of the leptospirosis outbreak at the time. If amoxicillin-clavulanic acid had been prescribed without testing for leptospirosis on the basis of the neutropenia and compromised gut mucosa, it is likely that the dog would have improved, and the diagnosis would have been missed. This could have had consequences for this dog since chronic kidney disease can become apparent sometime after acute infection. There are also wider consequences of not identifying and treating leptospirosis such as ongoing environmental contamination from the urine of dogs with chronic renal carriage and shedding of leptospires. When the diagnosis of leptospirosis is confirmed, a 2-week course of doxycycline is recommended to reduce chronic renal carriage.

It is possible that the chronic diarrhoea, low albumin, globulins, cholesterol, vitamin B12 and folate and ultrasonographic intestinal changes reflected a chronic enteropathy and that the oral prednisolone used to manage the hypoadrenocorticism had a positive impact on the gut. It is perhaps more likely that these features represented a more insidious onset of hypoadrenocorticism since hypoalbuminaemia and hypocholesterolaemia have been reported in patients with hypoadrenocorticism (Lyngby et al, 2016).

This case was unusual in having more than one cause for the acute clinical presentation. Jess responded well to the treatment of both conditions and has a good long-term prognosis.

References:

- Baumstark ME, Sieber-Ruckstuhl NS, Müller C, Wenger M, Boretti FS, Reusch CE. Evaluation of Aldosterone concentrations in dogs with hypoadrenocorticism. JVIM 2014, 28, 154-159.

- Lyngby JG, Sellon RK. Hypoadrenocorticism mimicking protein-losing enteropathy in 4 dogs. The Canadian Veterinary Journal, 2016, 57, 757-760.

- Schuller S, Francey T, Hartmann K, Hugonnard M, Kohn B, Nally JE, Sykes J European consensus statement on leptospirosis in dogs and cats. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 2015, 56 (3) 159-79.

- Snead E, Vargo C, Myers Glucocorticoid-dependent hypoadrenocorticism with thrombocytopenia and neutropenia mimicking sepsis in a Labrador retriever dog. The Canadian Veterinary Journal, 2011, 52, 1129-1134